%20(1).png?width=349&height=245&name=Untitled%20(1200%20x%20628%20px)%20(1).png)

Audiovisual Accessibility: Conversations with Archival Leaders About A/V Stewardship

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with leaders of archives and special collections programs about how they are approaching the stewardship of their audiovisual collections, and where these materials fit into their strategy and priorities. These conversations revealed that this continues to be an evolving area of practice, with variation in terms of how far work has progressed, but consistency in the kinds of issues repositories are contending with.

The challenges to stewarding these collections that the conversations identified are not new, they have been widely identified in previous work. What I did recognize as new was an evolving conception of what it means to provide access to A/V collections, and the tools and workflows being deployed to address access needs.

Where Collections Stand Today

The state of audiovisual stewardship varies considerably across institutions. Some organizations have achieved a solid understanding of the A/V materials within their collections, with clear priorities for further work identified. Others are still working towards the comprehensive baseline control that will allow them to make more informed prioritization decisions. Many fall somewhere in between, with good understanding of certain collection areas and less clarity about others, typically prioritizing digitization and preservation work based on high subject interest or user demand.

No matter their state of stewardship progress, the list of other challenges to stewarding these collections were consistent across institutions:

- Volume. The sheer quantity of audiovisual material makes it difficult to know where to start, and directly connects to cost concerns for reformatting and digital storage.

- Cost. Reformatting and digital storage are expensive, and storage costs are increasingly coming under scrutiny by central IT departments.

- Staff. Audiovisual work requires specialized skills, and in many cases, there's simply more work than current staff can accomplish.

- Rights. Copyright and performance rights create legal complexities that are messy to untangle, particularly when working with risk-averse counsel.

- Physical deterioration. Many institutions still face less-than-ideal storage conditions for aging media formats, creating a reformatting race against time.

Ultimately, providing equitable access is the end goal of stewardship, and online access is becoming the standard expectation for modern users. What it means to provide online access is evolving, as both legal requirements and values-driven practice broaden our conception of accessibility and what we want to provide our users.

Accessibility: Compliance and Values

In the US, this evolution is being at least partially driven by Federal Title II accessibility requirements for websites that will go into effect in 2026, and similar laws are in place in Canada. When asked about Title II requirements, the responses were remarkably consistent: nobody feels like they're in great shape. Every institution is assessing risk and moving forward as they can, but the path isn't always clear. There are questions regarding what compliance looks like practically, and how archival collections fit into exceptions within the law. Many found their legal counsel to lean toward risk-aversion when assessing requirements, and not always in sync with the archival default toward access.

Despite legal ambiguities, there was a strong sentiment that creating transcripts and captions for A/V material is a responsibility that extends beyond mere legal compliance and aligns strongly with the kind of broad and equitable access archives want to provide, as well as supporting better discovery and important scholarly use and methods. As one archivist put it, accessibility work is something institutions should be doing regardless of the law. Still, legal requirements are undeniably shaping priorities and, in some cases, creating opportunities for institutional support and funding for this work that might not otherwise exist.

Most organizations have implemented workflows to create transcripts or captions programmatically as part of their reformatting processes for new materials, often working with digitization vendors offering this as a part of their services. However, sizable backlogs of legacy materials still need to be addressed. While transcription had been a source of anxiety and emerging practice just a few years ago, it has become a more standard part of both workflows and expectations.

AI Transcription Experiments

Nearly all the institutions I spoke with are experimenting with AI transcription and captioning tools, actively testing platforms like Otter.ai, Whisper, Trint, and others. It is a developing workflow for most organizations, still very much in an experimental stage.

While there is plenty of healthy AI skepticism in the field, transcription is a need people seem to feel comfortable addressing with AI tools. It is a task that has always been expensive and burdensome and does not require the specialized skill of archivists and librarians, and the benefits to accessibility align with professional goals and values. The technology has also vastly improved in recent years – while AI still struggles with things like accents and multiple speakers, it does an increasingly good job creating acceptable first pass transcriptions with a large percentage of English language recordings in our collections.

The challenge of scaling up work with AI tools while maintaining efficiency came up repeatedly. Quality assurance (QA) is still necessary to identify and correct inaccuracies, and is particularly burdensome and often a bottleneck in the process. Leaders expressed a clear desire for better interfaces and more streamlined workflows for the QA process. The current reality often involves copying and pasting between systems, manually checking accuracy, and spending far more time on review than the initial transcription. A few institutions mentioned experimenting with crowd-sourced quality assurance for AI-generated transcripts—essentially distributing the review work across multiple users or community members.

The people I spoke with are weighing benefits and resources, trying to assess how much QA work must be done before something can go online. This is an area where the perfect can be the enemy of the good – with limited QA staffing resources, is it better to put up a relatively accurate transcript than no transcript at all? The prevailing sentiment is that it is; people want to default towards access. One idea to address this surfaced: implementing confidence ratings that could be displayed to users alongside AI-generated content, providing transparency about likely accuracy levels so users can make informed choices about using these resources.

A Platform Designed for This Moment

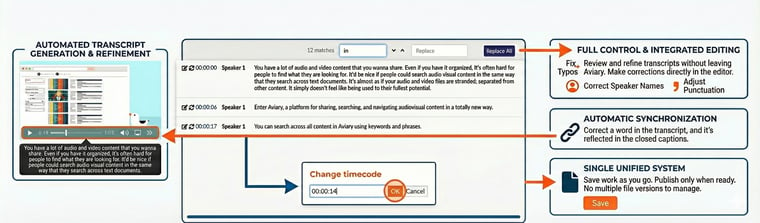

AVP asked me to have these conversations to help inform the future thinking about Aviary, but throughout I was struck by how much of its current functionality addresses the needs people articulated. Aviary is a cloud-based platform specifically designed for publishing searchable audio and video content. What makes Aviary worth considering in the context of these conversations is its built-in integration with multiple AI services for automated transcription, translation, captioning, audio description, and metadata generation to enhance accessibility.

For organizations striving to meet accessibility mandates, Aviary offers a streamlined, scalable solution that transforms how audiovisual collections are stewarded. The platform integrates advanced AI processing from services like OpenAI Whisper, AssemblyAI, Deepgram, Amazon Transcribe, and Cloudglue. From within the platform, users can leverage automated speech-to-text technology to rapidly generate baseline transcripts and captions, allowing organizations to tackle backlogs of AV collections much more efficiently. This addresses one of the key pain points identified in our conversations: the need for streamlined, integrated tools rather than disparate systems requiring manual coordination.

Aviary recognizes the importance of human-in-the-loop refinement for AI-generated content, and seamlessly facilitates the review and correction of AI-generated drafts in the platform. This built-in capability means that the quality assurance workflow—identified as particularly cumbersome currently—can happen within the same environment where transcripts are generated and stored. The platform supports multiple transcript formats whether created in the system or elsewhere, and can sync existing transcripts with audio. It also allows institutions to manage access permissions, deciding whether transcripts should be public or private based on copyright, privacy, or quality assurance concerns.

For institutions working toward accessibility compliance, Aviary extends beyond simple transcription to include complex accessibility needs like translation and audio description, ensuring that content is inclusive for all audiences, including those with either visual or auditory impairments. These services are also centralized into a single platform, as well as displayed to users easily on a single player where captions, transcripts, and audio descriptions work in concert. In a moment when institutions are weighing what they can realistically do to address accessibility with the resources at their disposal, this has the potential to empower institutions to robustly meet their accessibility goals.

For institutions working toward accessibility compliance, Aviary extends beyond simple transcription to include complex accessibility needs like translation and audio description, ensuring that content is inclusive for all audiences, including those with either visual or auditory impairments. These services are also centralized into a single platform, as well as displayed to users easily on a single player where captions, transcripts, and audio descriptions work in concert. In a moment when institutions are weighing what they can realistically do to address accessibility with the resources at their disposal, this has the potential to empower institutions to robustly meet their accessibility goals.

Importantly, Aviary is a product made by and for the archives profession, and archival values are front and center in their approach to using AI. They are clear about the tools they use and why they’ve chosen them and the strengths and weaknesses of each, helping archives select the tool best aligned with their needs. And they are not trying to sell AI as a replacement for skilled human labor and expertise, understanding the need for human review of computer-generated content and building this into the workflows they support.

Many thanks to the archival leaders who took the time to speak with me and whose generous insights informed this post.